July 20, 2020

Administrator Seema Verma

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

200 Independence Ave S.W.

Washington, DC 20201

Submitted via https://www.regulations.gov

RE: Medicaid Program; Establishing Minimum Standards in Medicaid State Drug Utilization Review (DUR) and Supporting Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) for Drugs Covered in Medicaid, Revising Medicaid Drug Rebate and Third-Party Liability (TPL) Requirements

Dear Administrator Verma,

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the proposed rule Establishing Minimum Standards in Medicaid State Drug Utilization Review (DUR) and Supporting Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) for Drugs Covered in Medicaid, Revising Medicaid Drug Rebate and Third-Party Liability (TPL) Requirements.

The National Pharmaceutical Council (NPC) is a health policy research organization dedicated to the advancement of good evidence and science and to fostering an environment in the United States that supports sustainable medical innovation. NPC is supported by the major U.S. research-based biopharmaceutical companies. We focus on research development, information dissemination, education and communication of the critical issues of evidence, innovation and the value of medicines for patients. Our research helps inform important health care policy debates and supports the achievement of the best patient outcomes in the most efficient way possible.

NPC shares the administration's goal of shifting the U.S. health care system more toward value and believes that value-based purchasing agreements are one promising avenue for promoting patient access to innovative therapies.[1]

As CMS proposes new regulations that will have significant implications for programs of this type, we encourage the agency to consider long-term impacts on patient care, access to new and existing therapies, and biopharmaceutical and payment innovation. Value-based purchasing (VBP) agreements had not yet been envisioned when the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), Best Price, and other policies were first designed. As the health care system pursues opportunities to reward value, regulations and guidance must be reconsidered and updated to ensure that the stakeholders can work to achieve that objective.

NPC urges CMS to maintain flexibility in any rules related to value-based purchasing agreements. While some VBP arrangements are in place, these agreements are not in widespread use. To ensure further adoption, manufacturers, payers and others will need the flexibility to determine what payment structures work best to provide patients with access to innovative and life-saving therapies. We encourage CMS to continue to adopt policies that allow for further advancement of payment innovation and better patient outcomes for years to come.

Our comments address the following points:

- Medicaid Best Price remains a critical barrier to implementing VBP arrangements.

- Proposed changes represent a good first step, but ambiguities and operational challenges should be resolved.

- CMS should consider more simplistic and less burdensome approaches to resolve Best Price issues.

- Other issues need to be addressed for increased uptake of VBP arrangements.

- Proposals not directly related to the transition from volume to value should be uncoupled from proposals to enable payment innovation.

- Patient access to cost-sharing assistance should be protected to promote medication adherence.

- Important innovations such as combination medicines and new indications approved as new medicines provide value to patients.

Medicaid Best Price Remains a Critical Hurdle to Implementing VBP Arrangements

Changes to Medicaid Best Price are necessary for further adoption of VBP arrangements. An online survey and series of in-depth qualitative interviews with over two dozen representatives from payer organizations and biopharmaceutical manufacturers revealed a variety of challenges that participants highlighted as factors that impact value-based negotiations. For example, manufacturers frequently cited challenges arising from data collection and evidence development, while payers noted that coming to financial terms could be challenging. However, Medicaid Best Price was cited by over two-thirds of those surveyed as a major reason why negotiations for value-based arrangements fail.[2] Therefore, NPC believes that addressing Medicaid Best Price policies will be vital to promoting the use of value-based purchasing arrangements.

Five Problems Arise for Value-Based Arrangement Due to Best Price Regulations

NPC research and partner research with the MIT NEWDIGS Financing and Reimbursement of Cures in the U.S. (FoCUS) consortium identified five issues related to current Best Price regulations that impede the use of value-based payment arrangements.[3],[4],[5][6] We describe these challenges and offer examples below.

- First payment problem: Annuity payment approaches spread payments out over an agreed-upon period. However, under current regulations, the first annuity payment sets Best Price and drug average manufacturer price (AMP) for inhalation, infusion, instilled, implanted, or injected drug (collectively referred to as "5i drugs") at a percentage of the actual costs. Non-Medicaid payers have indicated a desire to pay for some one-time gene therapies over several years rather than as a one-time payment. For example, payment for Zolgensma to treat spinal muscular dystrophy could have annuity payments spread over five years. Under current rules, the price of such a treatment would be defined as the individual annuity payment, not the total payments, leading to the Best Price set at a fraction of the actual price of the therapeutic.

- Single patient or per patient problem: A value-based discount that is determined by how an individual patient responds to the therapy could set a new Best Price under current regulations, even if there are multiple patient lives covered by the contract. For example, if a payment for a therapeutic is 100% dependent on a successful outcome, there is a significant risk of having the Medicaid Best Price set to $0 under the current rules. If one patient fails treatment (regardless of how many patients are in the plan) and the plan receives a 100% refund for that patient, the effective price of treatment would be $0 and would set Best Price at that level for the quarter.

Similarly, for chronic care VBP agreements focused on the total cost of care per patient, there could be similar impacts. For example, if the inpatient, outpatient, or emergency department visits were higher than anticipated in a diabetes care VBP agreement based on the total cost of care for an individual patient (with the plan receiving a 100% discount for patients not meeting total cost of care requirements), the Best Price for that diabetes treatment would be $0 for that quarter despite other members with diabetes in the plan having improved outcomes.

- Small population problem: Therapies intended for a small patient population mean that a payer may have very few patients under a contract. The outcomes for a single patient can have an outsized effect on Best Price. For example, a plan providing coverage for orphan therapies, such as Luxturna — a gene therapy to treat inherited retinal disease — may have very few patients treated in each quarter. This could lead to highly variable Best Price and AMP if just one or a few patients are treated in a plan and have poor outcomes, despite the majority of patients enrolled in other plans having successful outcomes in that quarter.

- Three-year time horizon problem: Price reporting requirements are unclear for longer-term contracts or annuities that extend greater than three years. Potential curative therapies may require longer follow-up periods to track outcomes as part of a VBP arrangement. In the case of Luxturna, the long-term durability of the treatment could take several years to assess. Under current Best Price rules, tying payment to an outcome tracked for longer than 12 quarters would be problematic.

- Subscription payment problem: A subscription model negotiates a lump sum amount for a target level of usage, or in an extreme scenario, all usage over a period. While some subscription models may not meet the definition of VBP arrangements, those models that link to evidence-based or patient outcomes should be included in the definition proposed by CMS. These programs highlight and present several challenges. First, the potential for unit price volatility as the number of units utilized might not be consistent across price reporting periods. Second, if the negotiated number of patients treated exceeds the capitated agreement level, the price for additional patients treated could be considered $0, and thus resulting in a new Best Price for all Medicaid sales. Third, a lump sum agreement made in a particular context might result in a unit price that would not have been negotiated in a different context; tying subscriptions to unit prices could discourage utilization of a useful approach. Some state governments have begun directly contracting with manufacturers to provide therapeutics at a fixed rate. For example, a biopharmaceutical company with a broad product portfolio in the cardiovascular space could provide coordinated care at a fixed cost. Such a model would facilitate a target level of care for patients who may have hypertension, high cholesterol and/or angina and require multiple medications to reduce their cardiovascular risk. Depending upon the utilization for each specific treatment in each quarter, there may be fluctuating per unit costs under current Best Price rules.

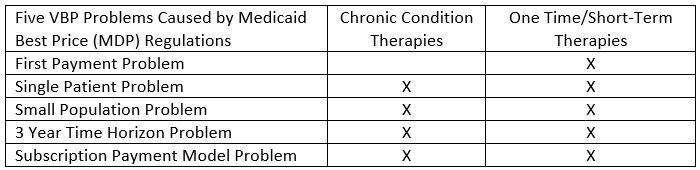

Each of these issues can affect Medicaid Best Price and impact therapies for chronic conditions differently from one-time therapies as outlined in the table below:

NPC recommends that any changes to Medicaid Best Price should address all five problems to remove barriers to the development and adoption of VBP agreements for both one-time/short-term therapies and therapies for chronic conditions.

Proposed Changes Represent a Good First Step, But Ambiguities and Operational Challenges Remain

To account for value-based payment arrangements that may lead to multiple price points for a drug or therapy available in a quarter, CMS proposes that a single drug may establish a "Best Price" for multiple price points based on the relevant or applicable VBP arrangement. This means that a manufacturer can report a set of Best Prices that would be available based on the use of a VBP arrangement(s).

NPC appreciates CMS' work to promote the use of VBP arrangement through updated regulations, including through proposed changes to the definition of Medicaid Best Price. As CMS notes in the proposed rule, manufacturers have raised issues and questions related to how value-based arrangements impact price reporting. While allowing for multiple best prices may address the challenge of small patient populations in implementing VBP arrangements, NPC is concerned that this proposal does not address other barriers faced by manufacturers and plans. NPC believes that policies should include flexibility for manufacturers and plans to design a variety of value-based purchasing arrangements. Greater flexibility would allow contracts to be tailored to the patient population, therapeutic outcomes, and risk levels most appropriate for the condition, plan, and patients receiving treatment. This proposed rule represents a good initial step but presents additional challenges to contracting parties and contains several ambiguities that could hamper the uptake of these VBP arrangements. NPC encourages CMS to issue additional rulemaking to clarify the intent of the proposal and resolve the significant ambiguities so patients can realize the full benefits of value-based arrangements.

NPC Supports Use of Both Evidence and Outcomes-Based Measures in VBP Arrangements, But Believes Concept of "Substantially" Is Subjective and Should Be Removed From the Definition

This rule proposes to define VBP as an arrangement or agreement intended to align pricing and payments to therapeutic or clinical value and includes evidence-based measures and/or outcomes-based measures. NPC supports the flexibility to allow both evidence and outcomes-based measures in these contracts. This will allow payers and manufacturers to tailor contracts to the chosen product, ensuring that the measures are appropriately matched with the value a therapy can provide. However, the proposed definitions link to a medicine's actual clinical performance or a reduction in medical expenses and may not encompass the full potential value for the patient. As CMS has noted, outcomes-based measures can also include "observing and recording the absence of disease over a period of time, reducing a patient's medical spending, or improving a patient's activities of daily living thus resulting in reduced non-medical spending." We encourage allowing payers and manufacturers to negotiate a broad set of outcomes-based measures, including both medical and non-medical spending.

Additionally, CMS is seeking feedback on the interpretation of "substantially" in the definition of VBP arrangements that links cost or payment or a product to evidence- or outcomes-based measures. NPC is concerned that establishing a threshold for what is "substantial" may discourage the use of VBP arrangements. Diverse clinical conditions may have different thresholds based on the availability of clinical or surrogate markers, the ease of data collection, and whether the VBP-eligible treatments represent a large enough share of health care spending to be sufficiently worth the effort.[7] Further, individual biopharmaceutical manufacturers and health plans have varying risk tolerance levels. Setting arbitrary levels to define "substantial" is unlikely to satisfy all conditions, biopharmaceutical manufacturers or health plans, thereby discouraging, rather than encouraging, value-based purchasing agreements. NPC suggests that CMS eliminate the "substantial" definition and threshold from the proposed rule.

- Rather than using a "substantial" threshold to protect Medicaid financial solvency, we suggest that CMS use the following two-prong approach. First, CMS should mimic the current approach of setting Medicaid Best Price for branded therapies by using the maximum of the statutory minimum (e.g. 23.1% for branded agents) or the Best Price as established under the new proposed VBP rules. This would provide the Medicaid program with the necessary financial protection and would give manufacturers and non-Medicaid payers the flexibility to contract around their needs should they decide to participate in a value-based arrangement.

Second, CMS should focus on removing barriers to state Medicaid programs entering VBP agreements by scaling up CMS grants to state Medicaid agencies to develop the capabilities and capacity to design, negotiate and implement these agreements. There is a meaningful learning curve to establish value-based payment arrangements and create the data infrastructure required to design, negotiate, and implement these arrangements. Grants have enabled some adoption by states. More will be required to scale such arrangements.

Finally, given the challenges to establish metrics and states’ varying abilities to collect data and implement such contracts, manufacturers must be assured that offering a VBP to a state Medicaid agency is voluntary and not required by the proposed regulation. NPC urges CMS to confirm that the choice to utilize the multiple Best Price approach or the bundled sale approach is voluntary on the part of the manufacturer.

Five Problems for Value-Based Arrangements Due to Best Price Regulations Are Partially Addressed

As described previously in our letter, any changes to Medicaid Best Price should address all five problems and the concerns for both one-time/short-term therapies and therapies for chronic conditions. We highlight below where further rulemaking is needed to resolve ambiguities and concerns.

- First Payment Problems Present Challenges for Annuity Models

Interest has increased in using performance-based annuity models for cell and gene therapies, especially in disease states where there may be a build-up of patients needing treatment. However, current regulations mean that the first payment in an annuity model could set both AMP and Best Price, as outlined above in the first payment problem. As additional cell and gene therapies become available, this problem will need to be addressed, so VBP arrangements are feasible. One potential approach is to calculate the discount under the VBP Agreement when the annuity terminates (e.g., either when the treatment is unsuccessful or when the treatment is successfully completed under the designated annuity timeframe). We request that CMS provide clarity on AMP and Best Price calculations related to annuities so manufacturers and insurers can use this contract design to ensure patients have access to these therapies.

Removing the Single or Per Patient Problem is a Positive Step, Ambiguities Need to Be Addressed

CMS provides two examples. In the first example, a Best Price is calculated using the bundled sales approach where discounts would be allocated proportionately to the total dollar value of the units of drugs sold under the bundled arrangement. In the second example, CMS employs a multiple Medicaid Best Price approach under which states would enter into a VBP agreement with the biopharmaceutical manufacturer. The terms of the VBP agreement would match those individual Best Prices and the associated outcomes. CMS goes on to state that each quarter the manufacturer would report a "single Best Price" and a "distinct set of 'Best Prices,'" creating multiple Best Prices. The rebate paid would then depend on whether a manufacturer and state voluntarily use a particular VBP arrangement. Both approaches address the single patient problem through different mechanisms. Under the bundled sales approach, a single unit can no longer set Best Price. Under multiple Medicaid Best Price, a discount will be outcomes-based rather than set based on the poorest therapy response in the non-Medicaid market. NPC believes removing the single patient problem, or per-patient population barrier is a positive step; however, key ambiguities need to be addressed to make this change effective (see next section).

Ambiguities and Concerns Relating to the Small Population Problem Should be Addressed.

As written, CMS’ proposed changes have several significant ambiguities regarding how the Medicaid Best Price calculation mechanics will work under the new rule. Specifically, the proposal to report multiple Best Prices will introduce additional confusion into the market. Therefore, addressing these ambiguities is critical to both resolving the small population problem and broader adoption of VBP agreements. Key ambiguities that need to be addressed include:

- First, how and when will the bundled sales and multiple Medicaid Best Price approaches be applied?

- Second, how are the non-VBP agreement rebates applied?

- Third, how will multiple Medicaid Best Prices be operationalized? (discussed later in our comments)

We believe that there are several different potential interpretations of the proposed rule. We discuss the merits and challenges of three interpretations below:

- Interpretation #1. The "Single Best Price" represents the Medicaid Best Price rebate calculated for non-VBP agreements using current rules and regulations.

- Under this interpretation, states would choose between traditional Medicaid Best Price rebates and entering VBP agreements to access outcomes-based Medicaid Best Price rebates. This is one of two preferred approaches and allows states the choice of maintaining the current rebate structure or accessing new innovative VBP payment approaches. Allowing states access to traditional Medicaid Best Price rebates protects their financial solvency as non-Medicaid rebates have not traditionally exceeded the Medicaid Best Price statutory minimum (e.g., allowing states continued access to the statutory Medicaid Best rebate minimum reduces the risk of a decline in Medicaid rebate amounts). From a manufacturer perspective, it will encourage the adoption of VBP agreements in commercial markets as these changes address the single patient problem and small population problem described.

- Under this interpretation, states would choose between traditional Medicaid Best Price rebates and entering VBP agreements to access outcomes-based Medicaid Best Price rebates. This is one of two preferred approaches and allows states the choice of maintaining the current rebate structure or accessing new innovative VBP payment approaches. Allowing states access to traditional Medicaid Best Price rebates protects their financial solvency as non-Medicaid rebates have not traditionally exceeded the Medicaid Best Price statutory minimum (e.g., allowing states continued access to the statutory Medicaid Best rebate minimum reduces the risk of a decline in Medicaid rebate amounts). From a manufacturer perspective, it will encourage the adoption of VBP agreements in commercial markets as these changes address the single patient problem and small population problem described.

- Interpretation #2. The "Single Best Price" is calculated using the bundled sales definition.

- Within a VBP Agreement, the maximum discount and potential Best Price, would be calculated using the bundled sales approach, under which the discounts would be allocated proportionately to the total dollar value of the units of drugs sold under the bundled arrangement. Under this interpretation, CMS would need to clarify and describe how Medicaid Best Price resulting from non-VBP would be applied (e.g., would non-VBP agreement discounts be compared with bundled sales discount?). This interpretation represents an improvement that removes the single patient problem but does not remove the small population problem.

- For therapies with small patient pools, including orphan therapies and cell and gene therapies, many of these therapies meet the needs of rare populations. Therefore, any individual VBP agreement may have a single patient or only a handful of patients in each quarterly reporting period, which could create significant volatility.

- Limiting the calculation of Best Price using the bundled sales definition of a single agreement significantly increases the size of the patient population required to reduce quarterly Best Price volatility. In these cases, the total patient population has to be large enough such that a single VBP agreement has sufficient patients to reduce volatility. At a minimum, CMS should consider expanding the sales included in the bundled sales definition to include all VBP agreements of a similar nature. An expanded definition that includes all VBP agreements would better address the small population problem and would encourage the use of VBP agreements.

- From a practical standpoint, the proposed rule would encourage the adoption of VBP for therapies for chronic conditions with large patient populations. However, it would not improve the situation for high-cost, high-value cell and gene therapies, one of the intended goals of the proposed rule.

- For therapies with small patient pools, including orphan therapies and cell and gene therapies, many of these therapies meet the needs of rare populations. Therefore, any individual VBP agreement may have a single patient or only a handful of patients in each quarterly reporting period, which could create significant volatility.

- Interpretation #3. The manufacturer determines whether to submit a "Single Best Price" calculated using the bundled sales definition (e.g., the Best Average Drug Price per unit and strength under a VBP Agreement) or use a multiple Medicaid Best Price approach under which each state would be required to enter into a VBP agreement with the biopharmaceutical manufacturer.

- Under this interpretation, for each therapy, states would choose between traditional Medicaid Best Price rebates and a manufacturer-selected VBP option. Depending on manufacturer preference, the VBP discount option would either be a bundled sales average or the state would have to enter VBP agreements to access outcomes-based Medicaid Best Price rebates. This is the second of two preferred approaches and allows states the choice of maintaining the current rebate structure or accessing new innovative VBP payment approaches. This option protects state Medicaid rebates in a manner similar to interpretation #1. This choice is preferred to interpretation #2 because manufacturers of small population therapies (orphan drugs, cell/gene therapies) can select the multiple Medicaid Best Price option, which allows them to avoid the small population problem. However, our recommendation from interpretation #2 to expand the number of VBP agreements included in the bundled sales definition also applies. This approach addresses the single person and small population problem and is likely to encourage the adoption of VBP agreements in key market segments.

- Under this interpretation, for each therapy, states would choose between traditional Medicaid Best Price rebates and a manufacturer-selected VBP option. Depending on manufacturer preference, the VBP discount option would either be a bundled sales average or the state would have to enter VBP agreements to access outcomes-based Medicaid Best Price rebates. This is the second of two preferred approaches and allows states the choice of maintaining the current rebate structure or accessing new innovative VBP payment approaches. This option protects state Medicaid rebates in a manner similar to interpretation #1. This choice is preferred to interpretation #2 because manufacturers of small population therapies (orphan drugs, cell/gene therapies) can select the multiple Medicaid Best Price option, which allows them to avoid the small population problem. However, our recommendation from interpretation #2 to expand the number of VBP agreements included in the bundled sales definition also applies. This approach addresses the single person and small population problem and is likely to encourage the adoption of VBP agreements in key market segments.

- NPC Supports Three-Year Revision Window for Best Price and Average Manufacturer Price

In the rule, CMS proposes allowing manufacturers to review Best Price and average manufacturer price (AMP) reporting beyond 12 quarters if necessary due to VBP arrangements. NPC supports this proposal as it will address the three-year time horizon problem outlined previously and gives manufacturers and insurers the flexibility to design value-based arrangements that evaluate longer-term outcomes.

Unique Design of Subscription Model Should Be Addressed

The subscription model, already in use by two state Medicaid programs, can create significant value for all stakeholders. However, because of the design, the price can vary substantially from quarter to quarter, so it may not be an appealing option in the commercial market. NPC encourages a further review of subscription models so that policies can promote use.

History has shown that regulatory ambiguity has hampered VBP agreements among payers and manufacturers due to various legal interpretations among individual companies. We suggest that CMS undertake further rulemaking to resolve these ambiguities.

CMS Should Consider More Simplistic and Less Burdensome Approaches to Resolve Best Price Issues

While the proposed rule offers a good first step in addressing concerns about Best Price, NPC is concerned that CMS did not consider the complexity that will result when there are multiple VBP agreements. Requiring a single VBP agreement for a therapy could hinder the adoption of these contracts due to the differing insurer outcome tracking capabilities and the varied risks insurers are willing to take on. A single contract structure may be too inflexible to meet varying capabilities, resulting in some commercial plans not entering into VBP agreements. CMS should consider an approach that supports multiple VBP agreement structures as this would provide the commercial market with much needed flexibility to address non-Medicaid specific needs. While we recognize that supporting multiple VBP agreements is not without challenges, operational difficulties for all stakeholders may exist when calculating, reporting and interpreting multiple Best Prices from several VBP agreements.The challenges remain significant under the assumption of a single VBP agreement structure as different reporting structures need to be developed for population-level versus patient-level based VBP agreements. The operational burden of determining, calculating, and then reporting multiple Best Prices across all these arrangements could disincentivize their use. In addition, the operational processes and associated requirements for states to enter in VBP agreements with manufacturers remain unclear. Greater clarity on the requirements for manufacturers and states to enter into VBP agreements is needed. Given the multiple and significant challenges, NPC recommends CMS consider alternative approaches to the proposed multiple Best Price approach (see below).

NPC, in partnership with MIT, is studying alternative approaches[8] and the potential impact of these approaches to various stakeholders. The leading alternative is a national pooling-type mechanism that allows the discounts across various VBP agreements to be pooled together to create an Average Best Price from the VBP agreements. Another option may be to pool outcomes (both successes and failures) across all VBP agreements and apply them to the most favorable VBP agreement to determine a VBP Best Price. NPC believes CMS should consider alternative approaches to Medicaid Best Price changes that would reduce the burden on biopharmaceutical developers and insurers participating in VBP arrangements.

Outstanding Issues Need to Be Addressed for Increased Uptake of VBP Arrangements

NPC is encouraged by the release of this proposed rule as a first step toward addressing the barriers to VBP implementation. However, CMS should address the outstanding issues described that are crucial to the development and implementation of VBP agreements.- Small Population Issues Remain for 5i drug Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) Calculations

Average manufacturer price (AMP) is a key component in the calculation of Medicaid drug rebates. The AMP calculation for 5i drugs is unique since insurer discounts, such as those under VBP agreements, are included. For a 5i drug with a small patient population, there could be significant volatility in the AMP from one quarter to the next, depending on which patients are covered under a VBP agreement. This, in turn, would cause the Medicaid rebate amount owed by manufacturers to fluctuate. This problem is particularly acute for chronic therapies and cell and gene therapies.

The net impact of the changes in AMP, and therefore the Medicaid rebate amount, could disincentivize the use of VBP agreements for these therapies as manufacturers may struggle to deal with the implications of the uncertainty. Solutions, such as updating the 5i period to extending the Medicaid rebate period beyond the calendar quarter, should be explored, especially as these small population therapies continue to encompass a growing share of U.S. health care spending. NPC recommends that CMS consider these and other possible solutions to address this problem so manufacturers and insurers can develop VBP agreements and ensure patients have access to these vital therapies.

Further Clarity is Needed to Understand Impact to the 340B Ceiling Calculations

Under current regulations, the ceiling price for a drug under the 340B program is tied to the Medicaid drug rebate amount. This rebate amount, in turn, is impacted by Medicaid Best Price. NPC recommends that CMS, in conjunction with the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), clarify that policies for 340B will remain consistent. This is important for cell and gene therapies. Many providers and facilities providing these therapies are 340B-eligible. Ensuring stability and consistency as new VBP-related policies are adopted will ensure these providers can still provide cell and gene therapies while participating in the 340B program and potentially participating in value-based purchasing arrangements for these new and innovative therapies.

Inclusion of Indication- and Regimen-Based Pricing Should be Considered

The proposed definition for VBP includes "an arrangement or agreement intended to align pricing and payments to an observed or expected therapeutic or clinical value in a population." In the subsequent definitions related to evidence- and outcomes-based measures, these efforts focus on observed or existing evidence.

- Within a VBP Agreement, the maximum discount and potential Best Price, would be calculated using the bundled sales approach, under which the discounts would be allocated proportionately to the total dollar value of the units of drugs sold under the bundled arrangement. Under this interpretation, CMS would need to clarify and describe how Medicaid Best Price resulting from non-VBP would be applied (e.g., would non-VBP agreement discounts be compared with bundled sales discount?). This interpretation represents an improvement that removes the single patient problem but does not remove the small population problem.

It is unclear how products that may have differential pricing based on the "expected" therapeutic value may be considered. Under today's system, most medicines have a single price, although each medication may treat multiple conditions and provide greater (or lesser) value for one condition compared with another. For example, TNF inhibitors treat many conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. The potential value of TNF inhibitor treatment is different for each condition. However, for most medications, there is only one price for all treated conditions. Indication-based pricing is a mechanism whereby the price for a medication varies by condition for which it is used.

Similarly, regimen-based pricing allows the price for a medication to vary based on the regimen or dose for which it is used. For example, certain cancer regimens may have substantially different dosages or regimens and, therefore, different pricing. For medications dispensed through the pharmacy, Medicaid best price rules may challenge indication- or regimen-based pricing.[9]NPC recommends that CMS provide clarity regarding the inclusion of indication and regimen-based pricing in definitions of value-based arrangements.

NPC recommends these additional concerns should be addressed, and stakeholders should be given an opportunity to provide feedback on the proposed solutions. Addressing these concerns can provide additional clarity to interested stakeholders and promote the use of VBP arrangements.

Proposals Not Directly Related to the Transition from Volume to Value Should be Uncoupled from Proposals to Enable Payment Innovation

NPC supports the agency's ongoing interest in transforming the health care system into one that better pays for value. Focusing on the significant steps to transform payment innovation among prescription drugs across the entire system has a significant urgency.[10] For these reasons, we believe the focus of further rulemaking and this guidance should remain on ensuring that innovation for payment and reimbursement keeps pace with medical treatment innovation. NPC recommends that CMS consider uncoupling proposals not directly related to the transition from volume to value and enabling payment innovation.

Patient Access to Copay Assistance Should Be Protected to Ensure Greater Medication Adherence

Patient out-of-pocket costs are an important factor in medication underuse, with an estimated 14% of insured Americans not filling a prescription or skipping doses of a prescribed medicine due to cost.[11] Patients who underuse medications are more likely to have complications, resulting in increased health care resource utilization (e.g., emergency department visits, hospitalizations, etc.) that is estimated to cost the U.S. health care system between $100 billion to $289 billion annually.[12],[13] Programs that have sought to limit patient out-of-pocket assistance have been shown to lower treatment adherence and increase patient discontinuation — unwanted effects that potentially increase costs and impact patient health.[14]

The proposed rule reflects a misunderstanding of both the manufacturers intent in providing copay assistance and their ability to prevent the application of copay accumulators or other tools that payers use to coopt that assistance after it is provided to patients. First, manufacturers' intent in providing copay assistance is to help patients afford their medicines. Patient cost-sharing has increased over the past decade, and manufacturer copay assistance is provided to help patients afford — often based on financial need — their medicines. Manufacturers do not intend for this assistance to be provided to health plans. Second, copay coupons are agreement entered into by the manufacturer and the patient. Besides not knowing when such programs exist, manufacturers have no way to prevent the application of copay accumulators or other tools that change how patient assistance is applied to the patient's insurance benefit. As CMS recognized, "the patient sometimes does not realize this [the manufacturer assistance does not accrue toward a patient's deductible] until the manufacturer copayment assistance runs out and the patient receives a significantly larger bill for the drug." [15]

Manufacturers cannot prevent plans from applying accumulators by "monitoring or placing parameters around the benefits or coverage criteria." Health plans are opaque about when these programs are being applied, and it is the health plans' discretion to ignore assistance to determine a patient's out-of-pocket spending through accumulator programs or copay maximizers. Therefore, the standard proposed by CMS is impossible for manufacturers to meet. As proposed, CMS could force manufacturers to reduce or eliminate copay assistance because they are unable to comply with this standard.

NPC recently commented on the 2021 Notice of Benefit Payment Parameters rule to express our concern with a policy that would encourage plan and PBM use of accumulator adjustment programs, even when patients have no other treatment options.[16]

We are concerned that the new proposal in this rule related to the Best Price exclusion criteria and accumulator adjustment programs undermine patient access to needed copay assistance. Further, CMS proposes this policy change and identifies the detrimental impact that accumulator adjustment programs may have on patients but offers no impact analysis in the proposed rule to better understand the potential patient harm and other unintended consequences of the proposal. NPC recommends that CMS not finalize this proposal due to the potential negative impact on patient access, especially at a time when access and affordability are particularly challenged.

Important Innovations Such as Combination Medicines with New Molecules and New Indications Approved as New Medicines Provide Value to Patients

Drug development is a complex process that often leads manufacturers to build on past successes when developing new medicines. An example of this is the development of combination medicines, which have been shown to improve adherence, increase efficacy, and reduce negative outcomes such as hospitalizations. This investment has paid off. A study of the seven top causes of death and disability 20 years ago demonstrates the significant improvements in patient outcomes. These conditions include ischemic heart disease, lung cancer, breast cancer, HIV, cerebrovascular disease and diabetes, each which has seen innovations in new molecules, increased use of combination therapy, and simplified treatment regimens. [17]

In the case of HIV, improvements in patient outcomes were attributed to public health programs and the development of highly active combination antiviral medications in a survey of 136 physicians.[18] mpirical data supports this perception. For example, a study of Medicaid enrollees with HIV found that patients on single tablet regimes were more likely to be highly adherent (≥95%), had fewer hospitalizations (23%) and reduced health care costs (17%) than those on multi-tablet regimens.[19]

These findings are not unique. Reduced medication complexity is associated with improved patient outcomes. For these reasons, manufacturers combine existing medicines into new treatments, or when developing new medicines, combine them with older medicines to maximize outcomes and reduce potential adverse effects. The FDA has encouraged this approach through guidance for the industry promulgated in 2014. [20]

Similarly, manufacturers undertake significant development when seeking approval of a new indication through a new NDC. This can include developing new forms of a drug for pediatric populations, or repurposing an old medicine for a new disease, such as many companies are exploring for treatment of COVID-19. We encourage CMS to recognize the benefits of these advances as it considers whether to finalize its proposed definition of line extensions.

Thank you for the opportunity to submit comments in response to the proposed rule. NPC looks forward to continuing to work with CMS to promote the incorporation of value into the U.S. health care system. We hope to continue these important discussions with CMS and other stakeholders and would be happy to meet to expand upon our comments and share our research.

Sincerely,

Michael Ciarametaro, MBA

Vice President, Research

National Pharmaceutical Council

Jennifer S. Graff, PharmD

Vice President, Comparative Effectiveness Research

National Pharmaceutical Council

[1] “Secretary Priorities.” https://www.hhs.gov/about/leadership/secretary/priorities/index.html#value-based-healthcare.

[2] Mahendraratnam et al. Value-Based Arrangements May Be More Prevalent Than Assumed. American Journal of Managed Care. Available at https://ajmc.s3.amazonaws.com/_media/_pdf/AJMC_02_2019_Mahendraratnam%20final.pdf.

[3] National Pharmaceutical Council. Regulatory Barriers Impair Alignment of Biopharmaceutical Price and Value. April 2018.

[4] MIT NEWDIGS. Precision Financing Solutions for Durable/Potentially Curative Therapies. January 2019. Available at: https://newdigs.mit.edu/sites/default/files/MIT%20FoCUS%20Precision%20Financing%202019F201v023.pdf.

[5] MIT Financing and Reimbursement of Cures in the US. Federal Policy Suggestions for Durable Therapies. Available at https://www.payingforcures.org/2019/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/P4C-Policy-Recommendations.pdf.

[6] MIT NEWDIGS. Incorporation of Value-Based Payment Agreements into the Calculations of Medicaid Drug Rebates. June 2019. Available at https://newdigs.mit.edu/sites/default/files/FoCUS%20Research%20Brief_2019F201v032%20-%20Medicaid%20Best%20Price_0.pdf.

[7] Dubois RW, Westrich K, Buelt L. Are Value-Based Arrangement the Answer We’ve Been Waiting for? Value in Health. 2020;23(4):418-20.

[8] This work is on-going, and results are expected in fall 2020.

[9] National Pharmaceutical Council. Regulatory Barriers Impair Alignment of Biopharmaceutical Price and Value. April 2018.

[10] Varma S. CMS’s Proposed Rule on Value-Base Purchasing for Prescription Drugs: New Tools for Negotiating Prices for the Next Generation of Therapies. Health Affairs Blog. June 17, 2020.

[11] Osborn R, Squires D, Doty MM, Sarnak DO, and Schneider EC. In New Survey of 11 Countries, U.S. Adults Still Struggle with Access to and Affordability of Health Care. Health Affairs. 2016;35(12):2327-36.

[12] Heisler M, Choi H, Rosen AB, et al. Hospitalizations and Deaths Among Adults with Cardiovascular Disease Who Underuse Medications Because of Cost. Med Care. 2010;48(2):87-94.

[13] Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, et al. Interventions to Improve Adherence to Self-administered Medications for Chronic Diseases in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):785.

[14] Sherman B, Epstein A, Meissner B, Mittal M. Impact of a Co-pay Accumulator Adjustment Program on Specialty Drug Adherence. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(7):500-505.

[15] 85 Fed Reg 32,298.

[16] NPC Comments on HHS Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters for 2021. Available at https://www.npcnow.org/newsroom/commentary/npc-comments-patient-protection-and-affordable-care-act-hhs-notice-benefit-and.

[17] Wamble D, Ciarametaro M, Houghton K, Ajmera M, Dubois RW. What’s Been the Bang for the Buck? Cost-Effectiveness of Health Care Spending Across Selected Conditions in the US. Health Affairs 2019;38(1):68-75.

[18] Wamble DE, Ciarametaro M, Dubois R. The Effect of Medical Technology Innovations on Patient Outcomes 1990-2015: Results of a Physician Survey. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(1):66-71.

[19] Cohen CJ, Meyers JL, Davis KL. Association between daily antiretroviral pill burden and treatment adherence, hospitalisation risk, and other healthcare utilisation and costs in a US medicaid population with HIV. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8):e003028.

[20] FDA, Guidance for Industry: New Chemical Entity Exclusivity Determinations for Certain Fixed-Combination Drug Products (Oct. 2014).